Image credits: WWD

The 2022 Met Gala took place on 2 May in New York City — a concentration of elite fashion, glamour, wealth, and prestige. Amongst the exclusive guest list of A-list celebrities was 20-year-old climate activist Xiye Bastida, a Fridays for Future NYC organiser and co-founder of NGO Re-Earth Initiative. Her attendance raised many questions, particularly one central one: What was a climate activist doing at the Met Gala?

‘She’s contributing to greenwashing.’

‘She’s fueling consumerism.’

‘She’s just there for clout!’

In full disclosure, Xiye is a friend and someone I look up to very much. This post, however, is not intended to take sides. Rather, I want to address some of the comments I’ve seen going round and more broadly, discuss the role of climate activists in ‘non-climate’ spaces.

First: What is the Met Gala? In short, it’s a fundraising event for the New York Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Costume Institute. Funds go toward the department’s ‘exhibitions, acquisitions, and capital improvements’. According to the New York Times, tickets cost $35,000 apiece and tables range from $200,000 to $300,000. The event raises eight-figure sums each year.

The Gala typically hosts around 600 attendees (pre-COVID). Vogue editor-in-chief Anna Wintour, also the Gala hostess, holds a tight monopoly of power over the guest list. Even after a company buys a table they don’t have complete freedom over who sits there; every single guest must be approved by Wintour.

Needless to say, this is an extremely, EXTREMELY exclusive event, open to only the highest-profile people. Past attendees at the Gala include multi millionaires like Beyonce and Jay-Z, as well as billionaires Kim Kardashian, Jeff Bezos, and Elon Musk. A 2015 article by Vocativ stated that ‘The combined net worth of the Met Gala’s guest list was larger than the GDPs of some countries.’ As Sophia Li phrased it, the Met Gala is a room ‘filled with names that have benefited from systems of capitalism, colonialism, and imperialism.’

Which brings me to the crux of this post: So what was Xiye doing there?

According to Xiye herself, she was there to ‘challenge people in [the Gala] to … realize the interconnection of their actions to not only the effects in the fashion world but what it means for peoples lives’.

In other words, she wanted to use the platform to spotlight the issue of environmental justice. It was an opportunity to tell fellow attendees at the gala, ‘Hey, you need to pay attention to this issue’, and also a way to tell viewers, ‘Fashion and celebrities aren’t all you should care about.’

‘Climate Justice must be present in EVERY space,’ she tweeted.

Xiye’s outfit was upcycled and paired with an Otomi Jade ceremonial necklace – a representation of the Indigenous culture and values that have guided her.

Political statements at the Met Gala are not new. Back in 2018, actress Lena Waithe wore a Pride cape as a way of championing LGBTQ+ rights. Last year’s edition saw the attendance of Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez with her controversial “Tax the Rich” dress.

Lena Waithe at the 2018 Met Gala

Image credits: Getty Images

Rep AOC at the 2021 Met Gala

Image credits: Kevin Mazur/MG21/Getty Images

Notably, AOC received a barrage of backlash for her appearance at the Met, many of which actually came from progressives who accused her of ‘aligning with the elites’. This is not unlike some of the comments Xiye received. By attending the Gala, some say that Xiye was ‘condoning’ the wealthy and their destructive, exploitative practices.

Ultimately, this boils down to a dichotomy that so many activists struggle with: Do work with the system, or do everything we can to resist it? Should we leverage opportunities to raise awareness (even if it means attending events in opposition to our personal values), or boycott them completely?

A year ago or even a few months ago, I probably would’ve gone with ‘boycott’. I saw activism as black-and-white; working with large corporations and institutions were a sign of conforming, endorsing, ‘giving up’.

I know people who still think this way, and I respect that. But I also think that there’s value in using high-profile events to reach out to more people—people who may not otherwise engage in discussions on climate justice.

Moreover, complete opposition can be problematic because there are far too many grey areas. It pits ‘us’ versus ‘them’ — but who falls into each category is ambiguous. Maybe you say that ‘them’ refers to billionaires and multi-millionaires and large corporations. Does that, then, mean we should boycott companies like Impossible Foods whose CEO said he wants to ‘use capitalism to kill meat’? Or, giving a more extreme example: What about politicians like Bernie Sanders who has significantly accelerated the democratic socialism movement, but purportedly has a net worth of $3 million through his Senate salary and book deals and sales? Heck, what about Greta Thunberg who’s white and born into a well-off family? Do we turn away from all of them too?

Like I wrote in THIS post, in an inherently broken system, every choice we make will be tied to unethical practices in one way or another. No brand or individual will ever be perfect. Complete resistance creates such high barriers to entry into the environmental movement that I fear we’re shutting more people out than we invite in.

Bringing this all back to the Met: From my point of view, all the buzz about Xiye was a win. It meant attention away from some celebrity’s extravagant dress, and instead towards activism and climate justice. Someone who maybe hadn’t heard about Xiye before may have looked her up, read about her work, followed her on social media, or read up on the harmful impacts of fashion on the climate. And a ll those represent entry points into the climate movement.

Image credits: Times Daily

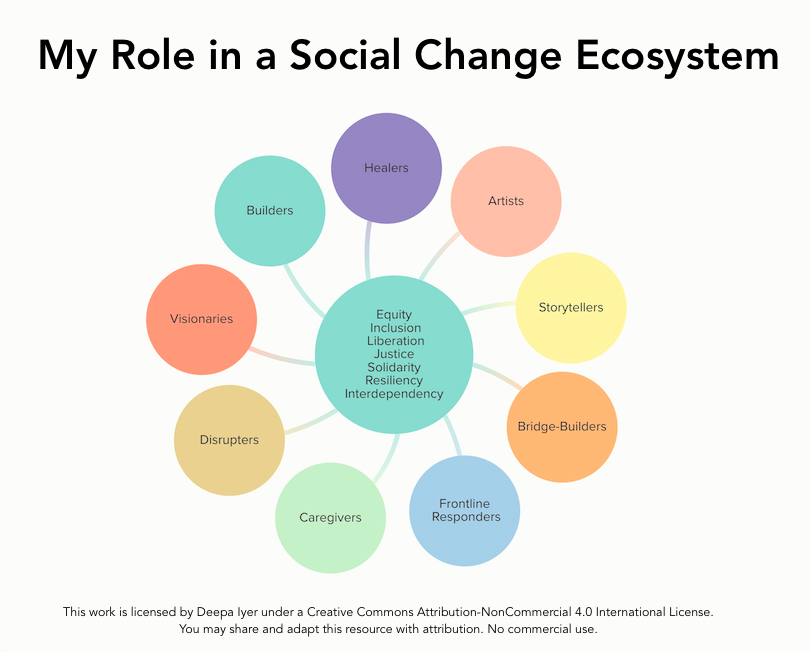

For those who say that Xiye was there for clout and ‘hogging opportunities’: The truth is that there are (and always will be) some activists at the forefront of the movement. That’s the nature of the social change ecosystem: You have storytellers and disruptors who have to put themselves out there, but also weavers and caregivers and healers whose work may be more behind-the-scenes. You have leaders and followers. ALL are needed—but everyone has different strengths and comfort levels. To some degree, I don’t think it’s inherently bad that some activists have more followers than others, or receive more speaking opportunities than others. For sure, it’s important to ‘pass the mic’ (especially to communities who’ve historically been silenced!). But the most important thing, to me, is that activism should always be about the movement, not the individual.

Finally, I want to talk about how youth activists are constantly held to a MUCH higher standard than everyone else. It seems like people expect us to only do activism and nothing else — we’re expected to be serious all the time, we’re not allowed to have fun. Greta received a barrage of hate comments after she was filmed having fun at a climate concert; Xiye was criticised for all the photos she took at the Gala.

People forget that ultimately, we’re teenagers too, and just because we care about the climate doesn’t mean we can’t do “normal” teenager things or live out our lives. We don’t fault singers for doing things apart from singing — so why should activists only be allowed to do activism?

In closing, we all have different levels of ‘radicality’ and that’s completely okay. As much as we should try to push boundaries and sit with our discomfort, don’t let others dictate what you can or cannot or ‘should not’ do. Do what you believe in; there is no one right way of activism!

Ending off with this quote from Xiye: “I will challenge the institutions that I am part of to leave the world better than I found it.”

Leave a comment